From college students facing an essay deadline to professional bloggers trying to make a little cash, everyone who writes occasionally stares down at his creation and sees something dull and lifeless. So why is this problem so much worse for fiction writers, who often fail to find a fix?

Every writer who is not eternally delusional will at least once in his lifetime complete his latest masterpiece and give it a quick read to confirm its brilliance, only to discover that it sucks. The piece in question, perhaps a hard-hitting university essay on climate change or maybe a from-the-heart Facebook post on motherhood, will come across so flat that the only tears it will elicit come from the writer himself as he realizes it’s a colossal failure.

Often the writer grits his teeth and digs into a hearty rewrite, determined to whip the writing into shape by changing a few words and moving some others around. Much more revision usually follows. Still, the result will be the same. You’ve written the crap out of it, but it’s still crappy. You’ve poured your heart into it, but it’s still lifeless.

So what’s gone wrong? In most cases, the problem doesn’t lie with what you’ve written but what you haven’t written. In other words, your writing has come up short because you don’t have something to say or, at the very least, don’t have enough to say.

As a newspaper editor I had dozens of conversations with reporters returning from an assignment who would sigh and flip aimlessly through their notebook after I asked what their story would say. It was clear they weren’t sure. In almost every case, they needed to do more reporting before they were in a position to start writing.

These professional writers are not alone. Countless people facing a writing deadline begin typing before they’ve spent enough time gathering research and grooming their ideas. Often they lack the basic facts to support their argument or the emotional first-person interviews to bring it to life. Unable to draw meaning from inadequate research and interviews, they dump their energy into trying to write around glaring holes. What they need to do, of course, is keep digging and continue brainstorming, only stopping when all this fresh material comes together in an urgent sense of direction. At this moment, they will know exactly what they want to say. And they will feel the story or essay trying to claw itself into the light. Only when this happens, only when the controlling idea coalesces in startling clarity, is it finally time to sit down and write.

So, when it comes to fiction, this problem of flat writing stemming from a less-than-fully-formed creation should not be an issue, right? After all, fiction writers are just making this stuff up, so there is no reason for their work to land with a non-compelling thud. Yet it often does. And strangely, fiction writers are often the worst suited to address such a potentially manuscript-destroying setback.

The first thing they do when a scene comes up short is begin furiously rewriting. After all, rewriting is writing, and everyone knows first drafts are shit. And sometimes, that’s all the scene in question needs. But often, the flaw runs deeper, and no amount of beautiful language, intriguing characters, amazing metaphors and witty and realistic dialogue will bring it to life. So they try adding something, often action. Maybe a main character must get hurt or suffer a broken heart. Yet these panicked and contrived revisions still leave the writer unsatisfied and ultimately struggling to understand why.

Unfortunately, some fiction writers never discover the actual problem, usually because they are looking in the wrong place. Like students, bloggers and social media fiends whose work suffers from not enough to say, these fiction writers fail to realize their problem doesn’t lie in what they’ve written but instead in what they haven’t written. Specifically, it rests in a narrative structure lacking in at least one crucial way.

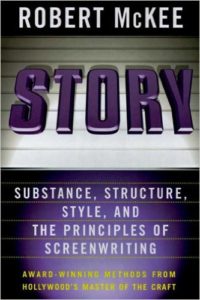

In most cases, their predicament can be boiled down to one four-letter word: risk. There is not enough at stake in what they’ve written, and no amount of rewriting will change that. Screenwriting guru Robert McKee describes it this way in his book, appropriately named Story: “Here’s a simple test to apply to any story. Ask: What is the risk? What does the protagonist stand to lose if he does not get what he wants? More specifically, what’s the worst thing that will happen to the protagonist if he does not achieve his desire? If this question cannot be answered in a compelling way, the story is misconceived at its core.”

In most cases, their predicament can be boiled down to one four-letter word: risk. There is not enough at stake in what they’ve written, and no amount of rewriting will change that. Screenwriting guru Robert McKee describes it this way in his book, appropriately named Story: “Here’s a simple test to apply to any story. Ask: What is the risk? What does the protagonist stand to lose if he does not get what he wants? More specifically, what’s the worst thing that will happen to the protagonist if he does not achieve his desire? If this question cannot be answered in a compelling way, the story is misconceived at its core.”Often, McKee says, the weak scene amounts to little more than exposition. And if its sole justification is to convey information about the characters, world or history, the scene should be trashed and the information woven elsewhere into the story.

Sometimes, a fiction writer’s beloved scene can be saved, but only by revising the structure of the scene and perhaps the entire novel. So how exactly?

Lisa Cron is a writing coach and author of Wired for Story: The Writer’s Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook Readers from the Very First Sentence. For fiction writers wishing only to read one book about their craft, this is the one I recommend.

Cron argues that our brains are hardwired to turn to story to teach us how to navigate the world, usually from the safety of our own home, in a survival-driven dress rehearsal for the future. She also believes humans are hardwired to recognize good and bad stories but not to write a good one.

She explains, “When a story enthralls us, we are inside of it, feeling what the protagonist feels, experiencing it as if it were indeed happening to us, and the last thing we’re focusing on is the mechanics of the thing. So it’s no surprise that we tend to be utterly oblivious to the fact that beneath every captivating story, there is an intricate mesh of inter-connected elements holding it together, allowing it to build with seemingly effortless precision.”

She explains, “When a story enthralls us, we are inside of it, feeling what the protagonist feels, experiencing it as if it were indeed happening to us, and the last thing we’re focusing on is the mechanics of the thing. So it’s no surprise that we tend to be utterly oblivious to the fact that beneath every captivating story, there is an intricate mesh of inter-connected elements holding it together, allowing it to build with seemingly effortless precision.”She perfectly describes a story as “how what happens affects someone who is trying to achieve what turns out to be a difficult goal, and how he or she changes as a result. As counterintuitive as it may sound, a story is not about the plot or even what happens in it. Stories are about how we, rather than the world around us, change.”

So, back to that flat scene. In any fiction you write, you need to ask what your protagonist wants (like finding love) and what inner issues or long-held belief (like fear of commitment stemming from a crazy college girlfriend who nearly destroyed his life) must be overcome to get it. Then you need to ask if the conflict your character faces in that scene is related to both his quest and his inner issue. If something feels off, like perhaps there’s not enough at stake, odds are the obstacles in your protagonist’s way are not relevant to either his quest or inner issue. And if what’s happening doesn’t matter in the big picture, why should anyone care? Which translates into: Why should anyone keep reading?

This means every single word you write in a novel must relate directly to the protagonist’s quest and the inner issue he must overcome, with the obstacles steadily increasing and the risk constantly rising. And remember, somewhere in your story is the sound of a ticking clock, a sense of urgency that pervades the entire manuscript.

Even once you’ve written an entire flawed manuscript, you can return to it and, scene by scene, make the necessary repairs. But it’s a huge job. It’s much easier to ask the tough structural questions before you’ve written a single word. It’s also easier to write detailed scenes if you have already outlined your main characters’ entire journey, beginning to end. Some fiction writers contend you can’t write the first sentence of a novel until you’ve written the last one, and they’re right about this paradox.

With my debut novel, Sneaker Wave, I created an outline of the entire novel and then wrote the final scene first. This way I knew the exact destination of my protagonist’s risked-filled journey, making it easy to determine if a particular stretch of road fit within my narrative structure, and whether there was enough at stake in that scene to make it sing.

In other words, before I sat down to write, I made sure I knew exactly what I wanted to say. And this helped make it much easier to try to write something captivating.